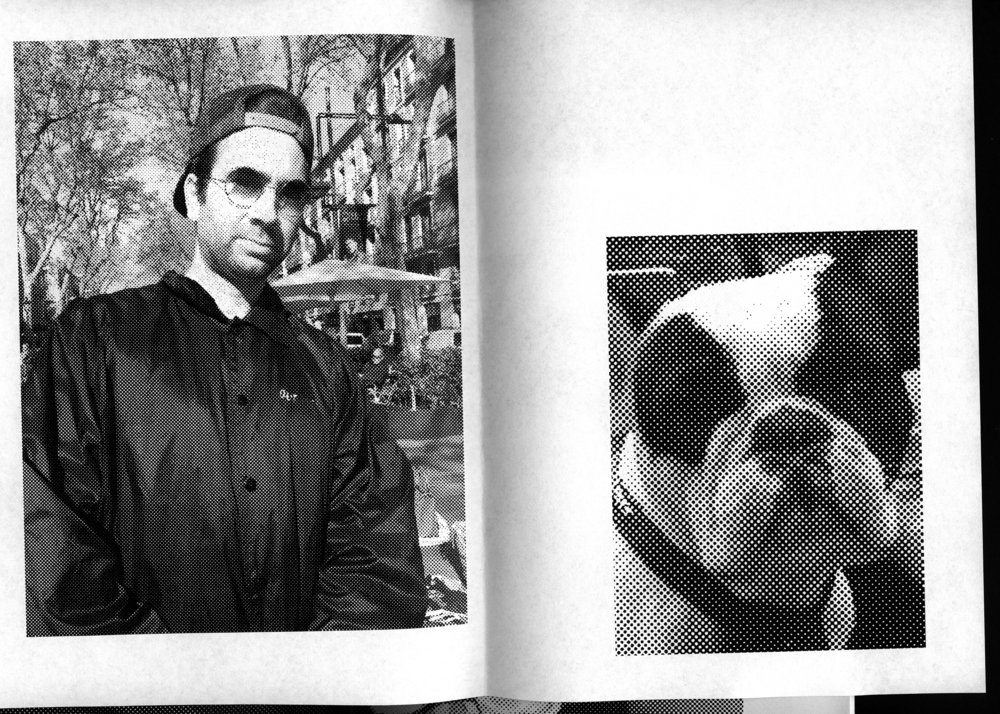

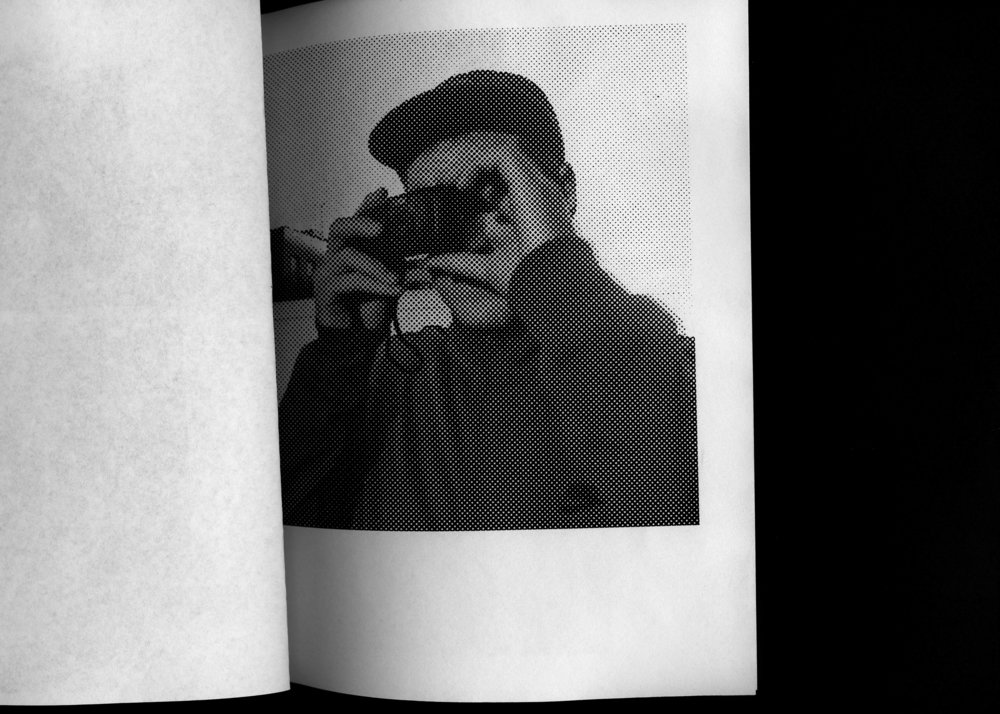

Interview by Yentl Touboul / Images courtesy of Grégoire Grange.

Grégoire Grange is a rather discrete individual.

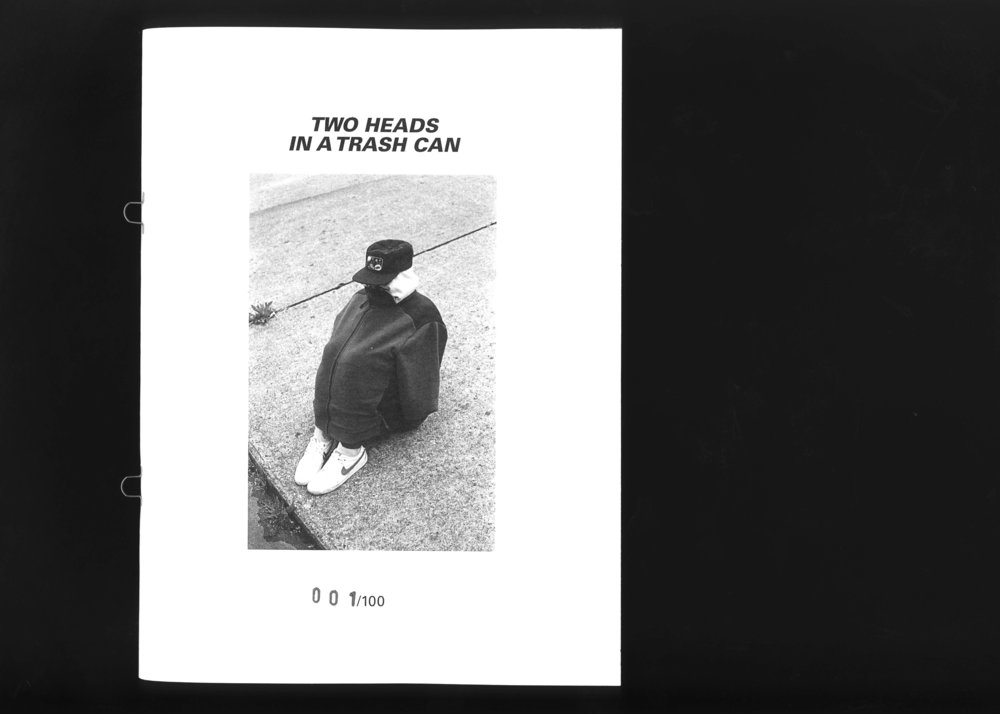

But if you’ve got a foot in the French skateboarding scene, you might be familiar with his name, or at least his work. Greg, as most of his peers call him, is a man of many talents. On top of being a published photographer (click here to check out some of his work), he runs a fanzine publishing company called Vague Books, under the banner of which he publishes work from the likes of Paul Grund, Ben Chadourne, and other staples in the European skateboarding scene. All of the above whilst working as an art director/graphic designer, being President of the Skateboarding Association of Bordeaux, and being a husband and soon-to-be father!

Needless to say that having the time to catch up with the man was a chance that we couldn’t turn down, even knowing that we were already above our maximum page count…

And here you have it. A conversation with Grégoire Grange.

WT: Greg, just to get a bit of background…who are you? Where did you grow up, and how long have you been based in Bordeaux?

Grégoire Grange: I’m a 45-year-old artistic director and photographer based in Bordeaux, France. In 2010, I joined my friend Sébastien Paquereau and we founded Bureau Parade. We mostly do artistic direction, graphic design and photography. On the side, I’m also developing a zine edition company called Vague Books. We’re mostly publishing projects that are somehow tied to skateboarding.

You’re something of a multidisciplinary artist, moving between photography, graphic design and print. How did it all begin?

Everything started with one of my best friends. He’s called Vianney and was managing a music label called Minitenor. I’d just finished studying English at uni and he asked me if I could take photos of bands and do album covers. That’s how I started working in the freelance world, without really planning to do so.

I didn’t go to art school or anything like that. Skateboarding and music brought me to where I am today. It enabled me to hang out with people who were going to art schools, and it’s thanks to them that I learnt all these things. I also need to mention Zoom, the photography magazine that ignited my first sparks of interest towards both photography and typography.

Is there one art form you prefer over the other?

Photography is the one I’m the most comfortable with. It doesn’t mean that it’s the one I prefer, but its production processes satisfies me easier compared to the others. Taking a photograph is easier and more convenient to me than drawing. But the most important thing is the project you’re working on. If the project motivates you, then the medium you use to realise it doesn’t really matter at the end of the day.

You now work independently but what jobs did you have in the past?

The only times I ever had proper jobs were summer jobs or jobs in skate shops. The only CVs I ever sent never got me that far, and I quickly decided that I wanted to work with what interested me. The possibility to produce something out of basically nothing and ending up selling it as an idea – that I always identified with. Of course, that’s still a dream situation and I ended up having to do a few small jobs, and working on the side to make it happen. But it teaches you a lot. After spending a week literally on your knees flower-picking, you suddenly become very motivated to live from working on artistic projects…

You used to occasionally work for French skate mags like Sugar, right?

I first started to work with Ride ON magazine. I was mainly doing illustrations for them at the time. Sugar happened more recently. I was signing off all my articles as “Barns”, which is the English word for my French surname, Grange.

I’ve heard you also worked for Playboy! How did that happen?

It kind of happened out of nowhere: a friend of mine moved back to Bordeaux after a long exile up in Paris, and asked if I wanted to take care of their artistic direction. We did the 6 issues we signed for, and another studio did the next 6 ones. It’s pretty unreal to have an email address ending in ‘@playboy.com’, and having access to this huge quantity of resources, interviews and original illustrations.

When did you first discover skateboarding? What’s your earliest memory?

I discovered skateboarding in ‘89. I first got hooked by surfing; I think the first magazine I bought was Surfing. I then stumbled upon a ‘Penny’-type board in my neighbour’s garage. We would ride it like it was a surfboard, blasting garden hoses and getting barrelled under the parasols on our terrace. I then discovered Surface magazine, a crossover between windsurfing, BMX…and skateboarding! I first bought a board from the local grocery store, and then transitioned to something more decent when I discovered Balibongo and Beach Break, some of Bordeaux’s first skate shops. I got my first proper board there. A Natas Kaupas with Mini Rats Powell Peralta wheels. I can still smell the varnish and the glue from this board. They’re rooted in my mind!

How did you come to be friends with the likes of Ben Chadourne & Paul Grund?

Paul is from Mont de Marsan, he moved to Bordeaux for uni. We used to skate together and he used to always ask me why people were so weird there when he first moved up. Ben is from Bordeaux and we always hung out together. We were filming, taking photos for each other and one thing led to another. We talked about it and my office became a place to exchange and work together. All of Paul’s zines were scanned and edited in this office, and most of Ben’s videos have been also edited here. Working on zines together came into the equation naturally, and we’ve been having fun together doing so ever since.

What led you to start Vague Books?

I always had close ties to magazines and everything related to print. When I first started skating, I received California Cheap Skate catalogues. It felt like having an open window on California. They had all the newest boards and products you could dream of. They were magical. I think these mags really developed my attraction to graphic design and print. Doing fanzines is easily related to this. Also, fanzines are not magazines. There’s a closer link with the person whose work you’re publishing, so you need to create a relationship based on reflection and dialogue about the the project’s objectives, and what you want to show.

What’s the process behind making the zines? Do you deal with the graphic design and layout or do the photographers know what they want?

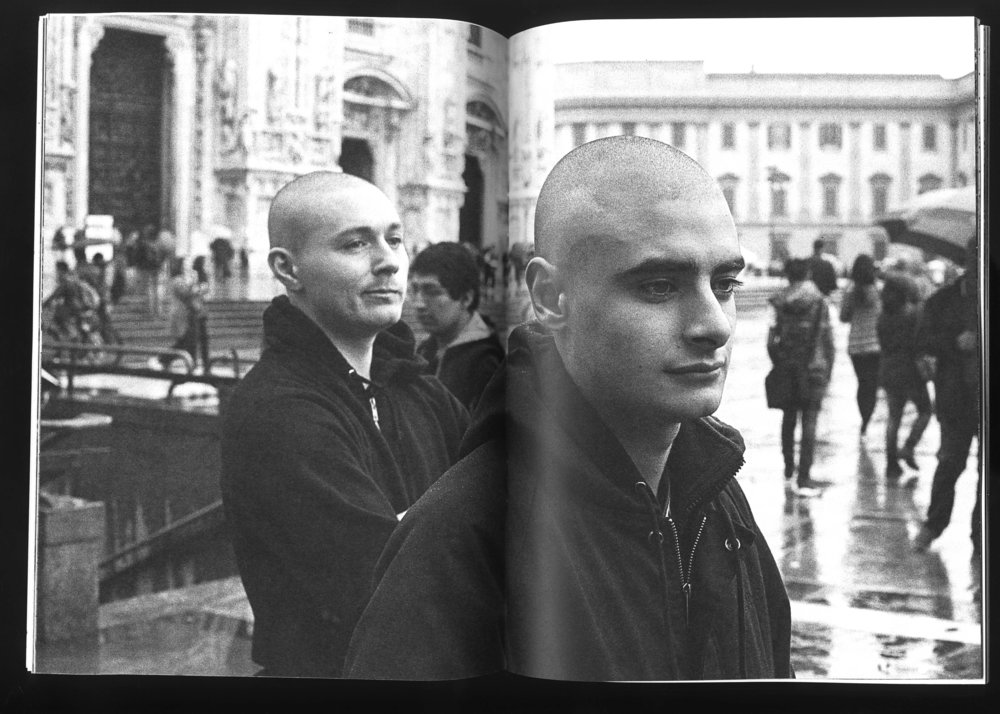

If photographers have an idea about what they want, they usually take care of everything. That’s what happened with Paul’s latest zine (Vague #6) – he did everything, from taking the photos, choosing the format and doing the layout. He came to a point where he knew which work he wanted to show, and he was also discovering Japanese photographers such as Araki or Masahisa Fukase. His zine really reflects that. When we discuss projects, things are always pretty free and easy; each person takes responsibility for specific tasks. Publishing is mostly based on exchange and finding a way of showing something in a limited 15cm x 21cm space.

What is coming next for Vague Books?

We’ve got something coming up involving Luc Borho. He is the artistic director of Sugar. He does a lot of photography parallel to his work for Sugar. We started working on a photo series he shot in Greasque, in the South West of France.

How did the growing importance of all things digital influence your work? Both in terms of the evolution of cameras/computers, but also regarding the omnipresence of internet.

It’s a relationship based on instantaneity. Everything is easy to produce, which isn’t to say that everything is of good quality within itself but at least your ideas are not limited by technical means. A phone, even with no internet, can enable you to take photos, draw, reframe stuff, write…The only hard thing when you have all of these tools available is to not fall into the trap of this frenetic type of production. You don’t want your work to just be a retort to the non-stop flow of so-called work thrown at us on a daily basis by social media and internet. This work is still a huge source of anxiety for me, but I recently decided to take part in it and turn my personal production into something more consumable to the public appetite – flexible and as a base for expansion.

What do you think about social media and its influence on artistic production?

It’s an incredible source of references and it is an amazing place to show your work. So it’s pretty positive in that sense. I’m not too sure that this period will last forever though. I tend to think this worldwide sensation of sharing everything is going to fade and that people will eventually return to being more private.

What advice would you give to young people interested in the publishing/visual arts fields?

What’s important is to see these disciplines as technical disciplines serving ideas as well as serving an overall project. To me, a designer is not an artist. It’s two different worlds. The amount of cultural references and the way they are put to the use within the project is what matters. The wider the influences, the more variations and diverse angles there will be.

Learn more about Vague and Greg’s work on their website & Instagram.

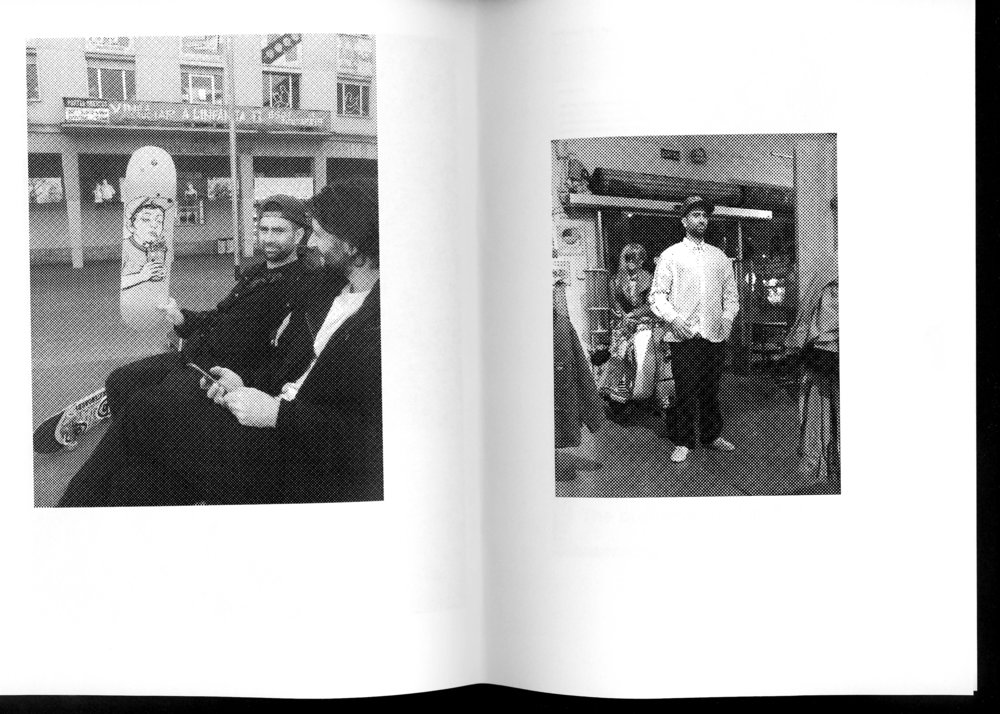

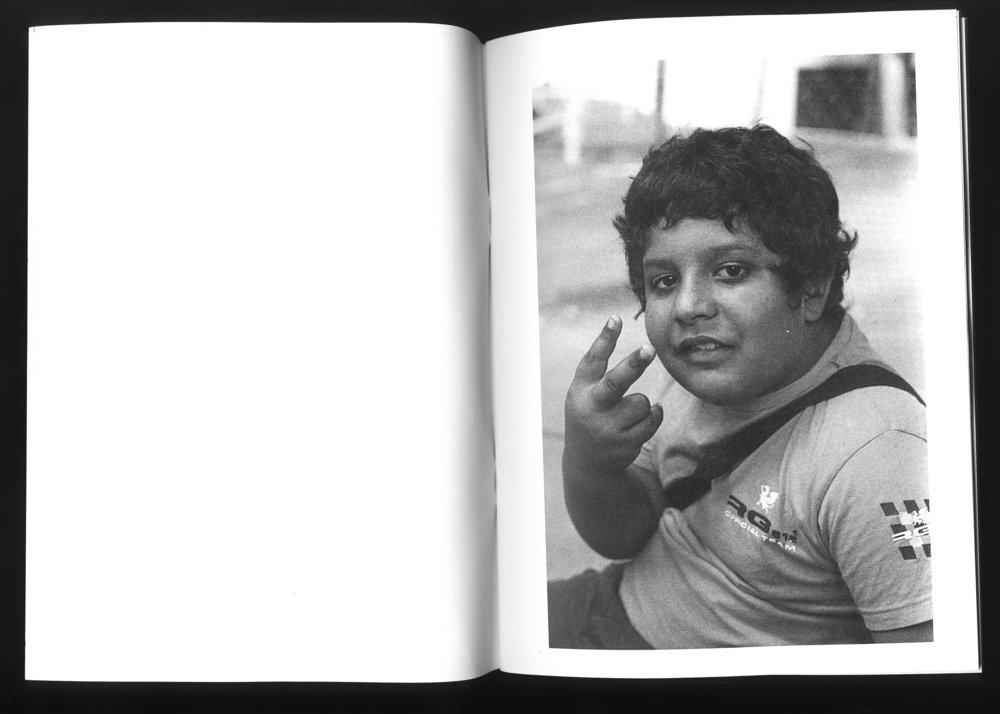

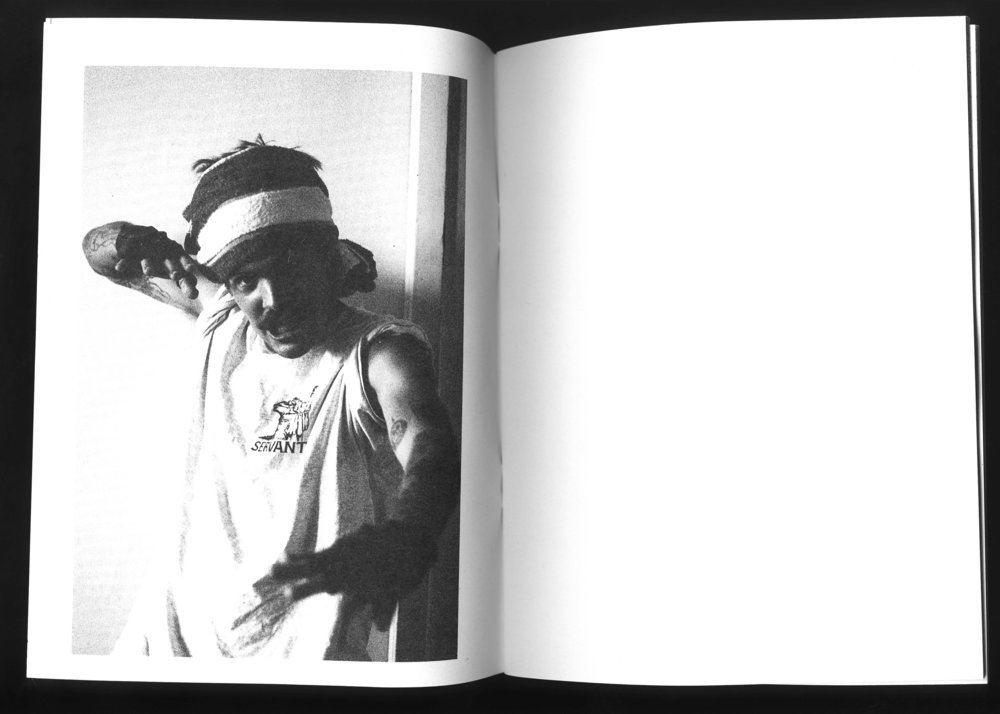

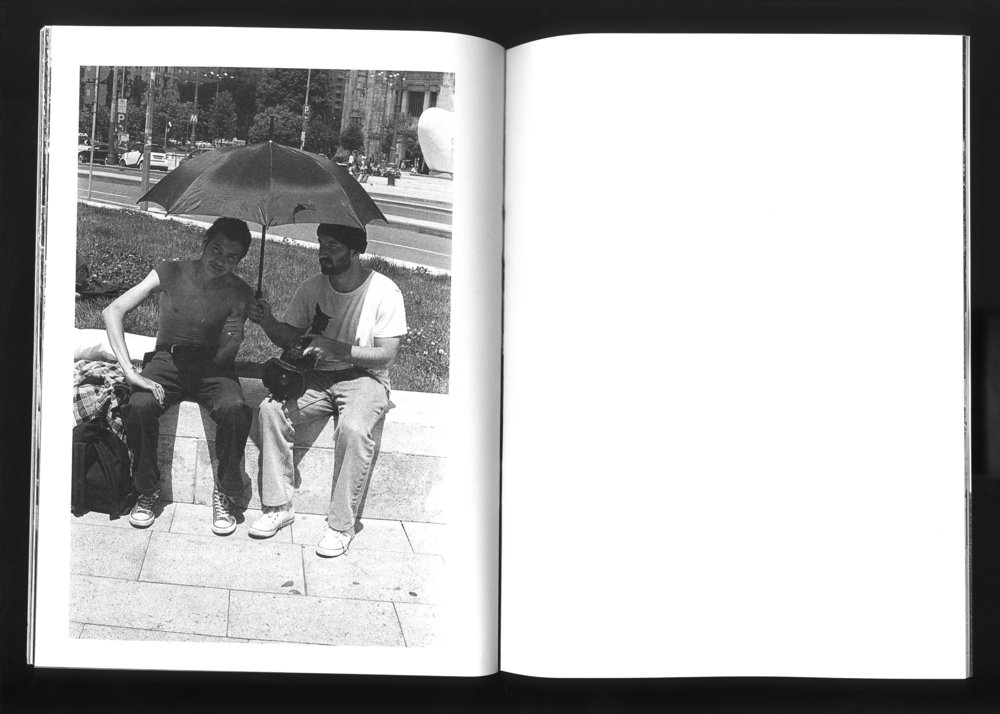

Kevin Rodrigues & Ben Kadow, extract from Vague #4 “Two heads in a trash can” by Paul Grund.