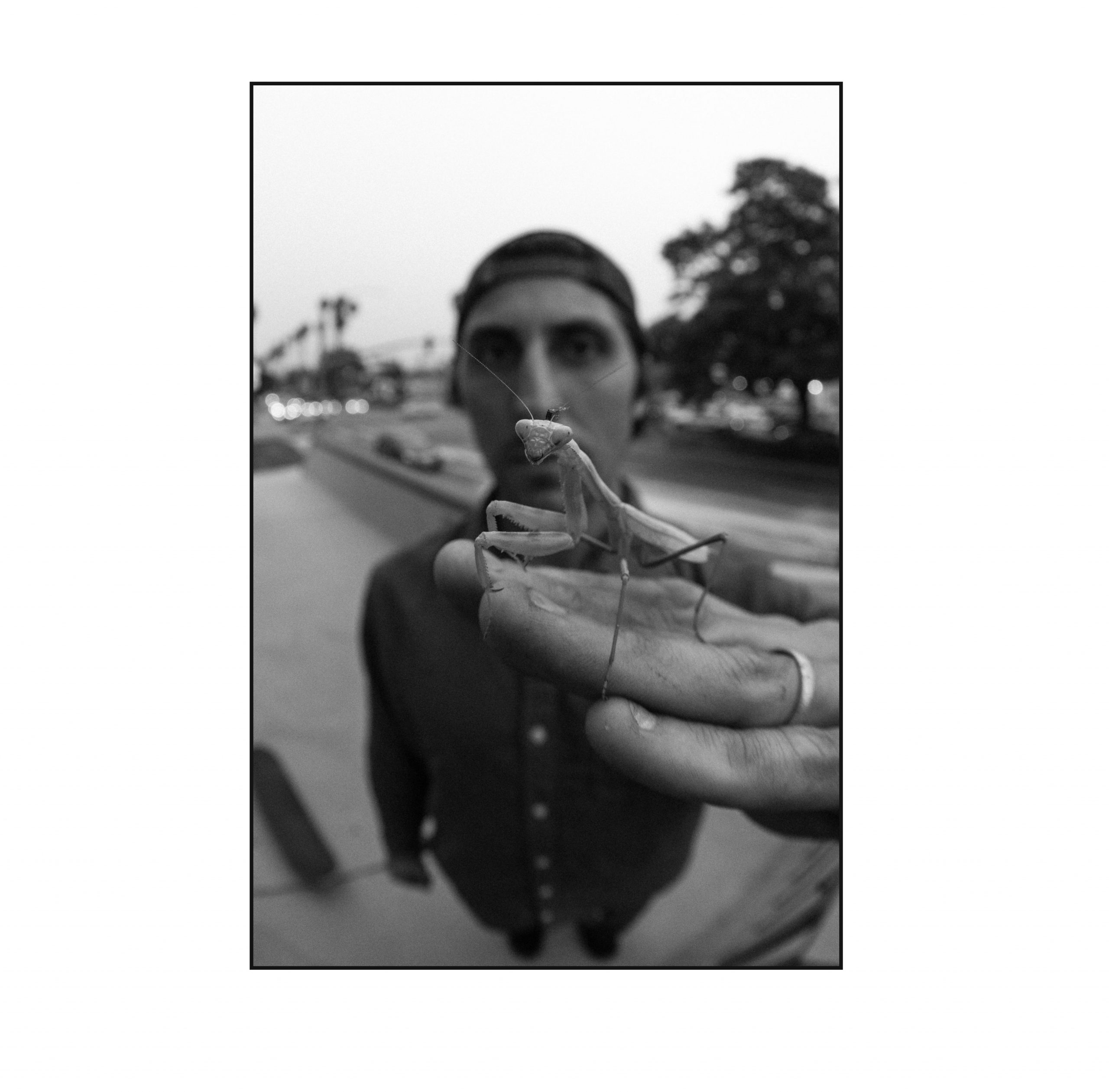

Interview by Matt Payne | Photography by Dakota Mullins and Matt Bublitz | 16mm frames by Matt Payne

Originally from the pages of Wasted Talent Vol. IX, published in July 2021.

To say we’re fans of Tom Karangelov would be an understatement.

Over the years he’s become one of our favourite skateboarders and if you’ve watched his String Theory, WKND, and Enter the Museum parts, it’s only fair to say that his approach is second to none. Tom’s powerful and precise skating, paired to his spot choice and subtle throwbacks to the 80s and 90s, makes him a unique character in the jungle that is the Los Angeles skate scene.

That’s why we were delighted to hear that he and Matt Payne were working on a short film together. Matt is quite simply a brilliant filmmaker, and has worked on some of our favourite surf videos in recent years. Think Chippa Wilson’s Octopus part, Globe’s Cult of Freedom series, Former’s Premium Violence and Luxury 29.99, as well as masterpieces of his own, such as his short film Arbutus, starring Nate Tyler.

The following interview celebrates the release of Weird Way Home, their joint project shot on 16mm around their shared home of Los Angeles. We’ll leave you with the two of them as they discuss the challenges of working on back-to-back parts, Tom’s passion for 80s cinema, the challenges of filming in LA, and much more.

Where are you from, Tom?

I’m from Serbia, but I grew up in Santa Ana, California. I then moved to Fountain Valley, but all my friends skated in Huntington Beach. So I claimed Huntington Beach growing up as a skateboarder. And then when I decided to move out on my own, I lived in Huntington for a few years. But for the last several years I’ve lived in Long Beach.

OK, tell me how you ended up being a pro-skater?

I was just like every other 13 year old… We just wanted to film and make skate videos like the ones we were watching. And then I just kind of kept filming with my friend Matt Bublitz, and we found out about this thing called Slap One in a Million. It was like a little contest. He submitted my footage and I ended up winning the thing. And that’s where I got to meet Jamie Thomas. He started flowing me boards and told me that if I wanted to take skating seriously, I had to send him footage to check in with him and stuff. So I got more into filming harder tricks and sending Jamie footage, and eventually going on Zero trips, dropping out of school, quitting my job. From there it just kind of all happened, from riding for Zero and so on.

I think it’s important because when I was a kid or up until now…when you see someone skating something different, it inspires you to try to think differently or find your own spot or idea… It’s almost like…I get motivated by somebody looking for their own things. And I’m like ‘Whoa, how did he find that? Where is that?’

And you just kind of started continuously filming forever?

Yeah. I’ve been filming for like ten or twelve years straight probably.

Why would you say it’s important to find your own spots, in L.A. in particular?

I think it’s important because when I was a kid or up until now…when you see someone skating something different, it inspires you to try to think differently or find your own spot or idea… It’s almost like…I get motivated by somebody looking for their own things. And I’m like ‘Whoa, how did he find that? Where is that?’ I don’t know how to explain it. I think it’s important to do that because hopefully it inspires someone who is similar to me and kind of sick of seeing the same stuff over and over… It’s just kind of cool to see different things where you live and how someone else views it.

Who would you say is like a good source of inspiration like that?

I really like that dude on Quasi Dick Rizzo because I’m guessing he lives in New York, but it looks like he’s skating parts of New York that I’ve never seen or he travels outside the city like 45 minutes in every direction to find stuff. Or Fred Gall…his Instagram posts show really cool things I’ve never seen. And I think he lives in New Jersey. So why is it so many skaters who live in New York can’t just go to New Jersey and find cool things, rather than skating blown-out stuff?

What about L.A. in particular? Why is it important here?

It’s important here because it’s been skated for like thirty or forty years. L.A. has been skated heavily so to see different spots and younger kids digging deeper, it’s inspirational to people like me. I think it’s important for those reasons. But to have that side of skating, you need the mainstream side of skating to exist as well, which is weird to think about… Like if everybody looked for spots, every single thing would be found and it would be impossible to show something new. It already feels almost impossible.

What’s your day normally like when you’re looking for spots?

When I look for spots, I just pick an area that I haven’t been to and I’ll drive around in circles for like, five to six hours. And then I always end up somehow being back in the same area that I started in. It’s hard for me to find areas where I’ve never been… Or like a section will be new. And then I’ll go back and realise I’ve been here before. But by doing that, I realise other things. I would drive past the Burger King from Back to the Future and I’d wonder like, are there spots around it? A lot of movie scenes have been filmed in L.A…I’ve talked about this before, but it’d be like ‘I think I heard Tupac has a house in this area’, so I might go look in that area and then track down Tupac’s house.

Where do you get inspiration for spots?

A really easy example I can think of is when I was watching the movie The Karate Kid and the whole thing takes place in Reseda California which is in the Valley… So I went to find the apartment that Daniel (the main character) lives in and then locate the high school he went to or like, the nightclub he danced at…so I just find those areas and find random spots around those movie sets.

So these weird 80s pop culture references are what you’re geeking out on? Sometimes you’ll just see random shit around those things?

I remember a really weird one. I haven’t seen the movie Adventures in Babysitting for a long time. And I remember we were driving through the Valley and I noticed this Chuck E. Cheese and I was like ‘Dude, I swear this corner of the building is in a movie.’ And I remember Googling ‘Chuck E. Cheese filming location’. And it was Adventures in Babysitting. And there was a sick spot like right by it. That’s kind of like a weird example of that happening.

But to have that side of skating, you need the mainstream side of skating to exist as well, which is weird to think about… Like if everybody looked for spots, every single thing would be found and it would be impossible to show something new. It already feels almost impossible.

You recently changed your board sponsor after being with a couple of different companies over the years. You’ve bounced from Zero to 3D to Skate Mental and now WKND. What’s it been like shifting over to WKND?

The change to WKND felt really natural because I’m really good friends with Jordan Taylor, Alex Schmidt and Grant Yansura who owns and films for WKND. So it just felt like the perfect place for me to be. I had thought about riding for them in the past but I’m really bad at asking people for things, especially with skateboarding. So it just happened like really naturally after skating with them a bunch. That’s like the natural progression of where I want to be. I don’t want to skate for any other company. I just wanna skate with dudes that I like, and they’re my age and we’re all into the same stuff. And Grant knows how to treat and take care of his riders. I think that’s really important.

Skateboarding encourages small do-it-yourself companies. How did Museum come about? What’s your goal with it?

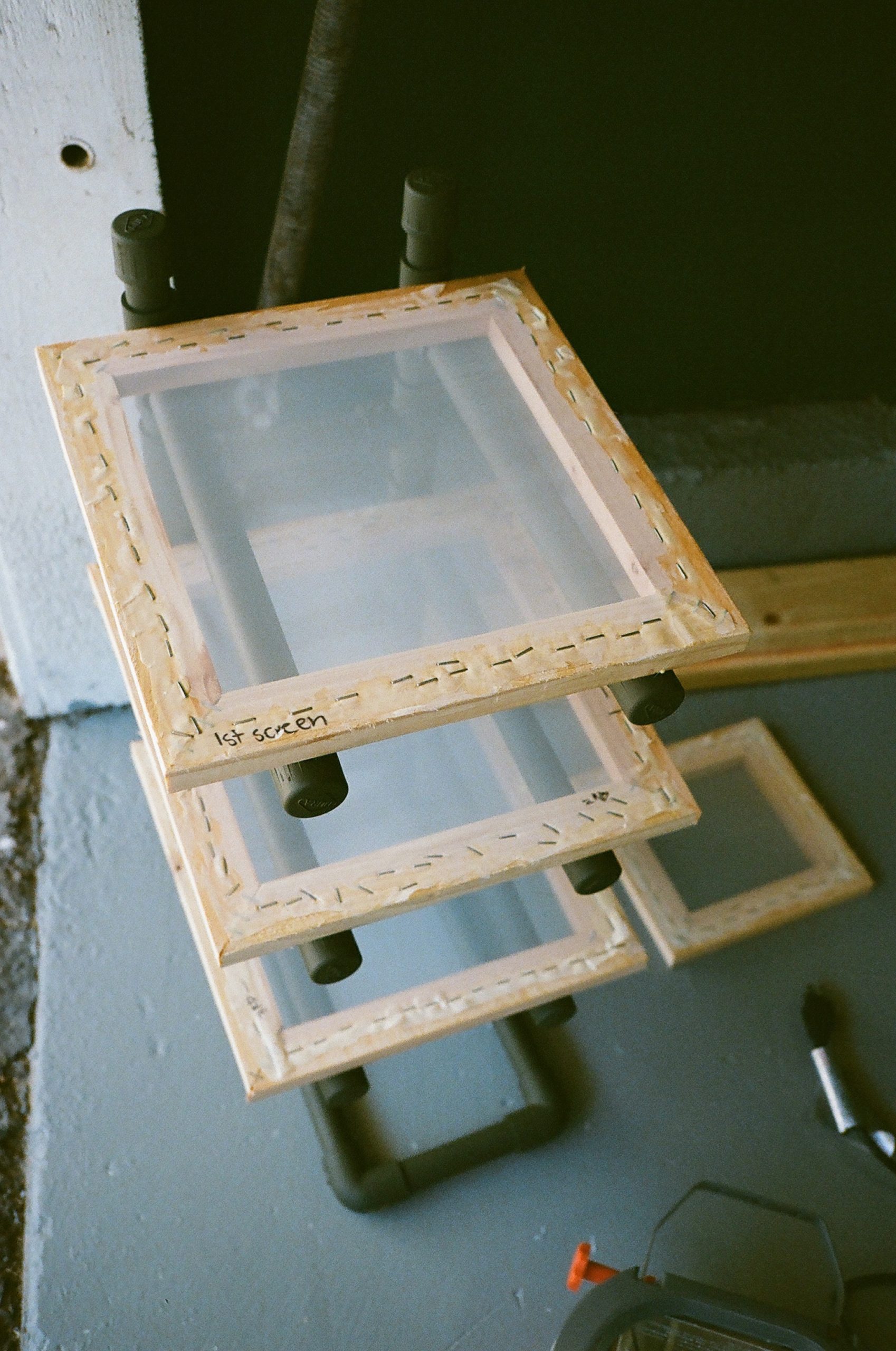

Matt Bublitz works for Thrasher, so I feel like he’s really busy most of the time. I was filming a New Balance part the last couple years. And I noticed that there were a couple kids coming up now that I was really stoked on from my area. So I was always just talking to Matt about the idea of like trying to do a video series with our own product to go with it. Because I had seen other people doing that and I got hyped on Carpet Company, which is two brothers who made a little successful business and now do things their own way. But I guess at the time when I wanted Museum to come out, I didn’t realise the world would be shut down because of a pandemic. So we had to kind of keep everything local. I think the idea behind it was like, let’s do something really sick and use Matt’s garage because he didn’t have anything in it and create something fun we could use to shine a light on the local kids that I like. But I still don’t know if it’s going to be an accessories company or what it is exactly. I just know I want to keep making little videos and have product tied into it. And through that I think it’ll grow into something.

Who’s in the Museum crew?

It’s me, Matt Bublitz and Avery Johnson. Just a little crew. I’m starting it small because Matt and I have to pay for everything we do. Eventually, when we go on trips, we’re going to have to pay for those, too. So I don’t want to blow up this thing too quickly. I want Matt and Avery and whoever else is involved to know what it’s like to start a cool small thing that we do ourselves, and on which we use our own resources. For example, spending our own money on product. I think there’s like an important lesson there that I didn’t get to see when I was younger because I grew up skateboarding at a time when it was run by these huge companies that had a bunch of employees. So it’s kind of cool, I’m learning a lot and hopefully Avery can see how everything works. It’s also me and Matt are learning about the start-up process lots too. And it’s cool how many people support us or back it or are down to help out or be involved. That gets me the most stoked, when people reach out to help us.

When you come up with a company, how do you find the vibe when it’s just this blank slate, from coming up with the graphics and narrowing down the vibe and spirit of the company? Like…you’re wearing a shirt with a dumpster on it as we speak. What inspires that and where do you get a point of reference to go in that direction?

I grew up watching 80s and 90s horror and sci-fi movies, but I feel like with all of that combined, I always knew I wanted to use TV as a theme in a weird way, which isn’t completely original, but I wanted to try to make it kind of original and strange. I guess there’s a direct connection with David Byrne or David Lynch, for example. Those two artists’ vibe combined for inspiration and mixed in with skating. And I know Matt’s really particular about what he wears and the things he likes. So I’ll draw like a million things and show Matt, then he won’t like any of them. And then we’ll just keep the process until one idea sticks, and slowly it goes from there. Narrowing down the vibe takes us talking and testing things out and then like making sure it doesn’t look cheesy.

I mean, you guys literally make all that stuff too, right?

For example, our upcoming Museum drop. My sister-in-law Gabby helped us pour all this candle wax into the mould that she made for a collection of Museum skate wax accessories. And with the range of tees, I sewed the tags. We try to screen print graphics too, but we actually got connected with this guy that runs a company called Monsters Outside, and he is super down to help us experiment. So I feel like through all this, we meet a bunch of people and it all helps the vibe come together for Museum. It’s still so small and it’s going to change after the Enter The Museum video series is done. I’m sure it’ll evolve into something else even weirder. I feel like I like really simple stuff that you work on forever and no one knows how hard you worked on it. And then it just comes out and, maybe no one even notices that it took like three times to move the TVs at like 5 am in the right spot for B-roll in the video. Where something you see in like two seconds really took 30 hours to make possible. I don’t know, little nuances like that are cool to me. So maybe it creates like a vibe and you just test everything and then you see where you want to go with it. It changes on its own. But I know the TVs are like an important part to me. And in skateboarding, I haven’t really seen that. I know a lot of music videos have had that art direction. I was probably inspired by a Tom Waits music video where he moved some TVs around.

I don’t know what those dudes were watching to get inspired to do that, but I think a lot of skate stuff looks to the past for inspiration. I think the past is guiding the future in a way. It just looks normal to skateboarders to see that look that’s been passed down from those old Alien videos and Habitat videos.

Filming is pretty hard and I know you film tricks of friends by yourself as well (maybe some people might not know that). But what kind of eye is needed to make a good part? And what sets certain filmers apart that you’ve worked with before, like Grant Yansura, Matt Bublitz or Chris Theissen?

I think the filmer and the skater have to just be on the same page and you have to trust the filmer. I know that when I film Matt I’m scared to get the lens hit and I’ve dropped the camera before so I’m not as comfortable moving the camera as close as I should. I’ll watch how I film Matt and I try to emulate what I would want to look like myself. When you film on RED cameras, you look slower for some reason, maybe it’s the frame rate or whatever, and you can’t get that close to the skater… Matt and Grant film with cameras that are handheld and can get really close to you while you skate. They both skate really well. So they’re both trying to make you look like what they would want to look like and vice versa. I would try to make Matt look like what I would want to look like. I try to be really close or have some weird angle on the trick. I like it when there’s action the whole time. Fast. That can make even fun stuff look gnarly, I think.

Cameras with certain looks are heavily intertwined with skate culture and you’ve probably filmed like a part on every format at this point. VX1000, HPX, RED and obviously Super 8 and 16mm film are woven into shooting as well. Why would you say it’s important to commit to one camera?

I think it’s important to keep the same filmer shooting most of your footage with the same camera just because it brings the vibe together. It’s going to look different if you pull from like 15 different filmers or different cameras. It’s like a movie, you want to be sucked into it. And I think when it’s all filmed and edited by the same person that you trust, that you have a connection with, it will come out exciting and fun to watch.

I feel like skate culture in general uses mixed media in a way that you don’t really see in any other industry, aside from surfing or music videos. There are so many different cameras to use and so many different lanes you could pick to make your vision happen. Why do you think skateboarding encourages using all those different formats?

We grew up watching Transworld videos for example and filmers like Greg Hunt making these things with cool cameras. You’d see a 16mm montage and then a VX1000 video part right after. And it created this certain vibe. I don’t know what those dudes were watching to get inspired to do that, but I think a lot of skate stuff looks to the past for inspiration. I think the past is guiding the future in a way. It just looks normal to skateboarders to see that look that’s been passed down from those old Alien videos and Habitat videos.

What’s it been like shooting skate tricks on 16mm over the past couple of years? How do you approach analog versus digital?

Shooting 16mm is the gnarliest format of all of them. I think it’s strange because it’s so expensive and limited to three minutes per roll, and in skating you never land anything right away. I never land any tricks quickly. So I know that there are certain times where if you’re trying to get the trick on film, I know I have to be quick…or we can vibe on the same level sometimes and accidentally get the trick on 16mm. And it’s a cool feeling because it’s unpredictable. Usually with skate filming, you’re just sitting there for hours pushing record on a digital camera and then you get it. Filming things this way is very strategic and hard but very fulfilling when it works out. And when it doesn’t, I just get so angry because I know I wasted so much money trying to get that trick on film (laughs).

It’s finite and it’s gnarly. You have constraints, especially when you’re shooting really hard tricks. So the skater and filmer have to be totally in sync when its on 16mm.

It’s definitely been really fun to try and do. It’s hard and I know anyone that has actually shot with that camera will know how hard it is to do well.

Can you talk about the story behind our short film Weird Way Home? Where did it come from?

When we first started hanging out, you were filming a lot of surf stuff on 16mm. And you told me that you always wanted to shoot skateboarding. Any time I would drive back home from L.A., I would take a weird way home because there would be so much traffic and maybe I could find a skate spot on the way back. I would just take a random street all the way back to Long Beach. You got really hyped on that and it ended up being the name of the project. And we just started filming random stuff while I lurked for spots or while skating. You came skating more and more while I was filming for my New Balance String Theory part. So you were there for a lot of sessions and you’d just be quietly in the corner getting tricks on film. In the beginning, you didn’t have a fisheye lens, so you’d be like, “Dude, I think I got that trick.” We would vibe on certain tricks. I’d be like, “Right here, Matt.” And you’d be like, “Should I roll on this?” And I’d be like, “Yeah, this try is the one.” And then it would work sometimes. A lot of times it wouldn’t work (laughs). You followed me pretty much through that whole video part and then sprinkled in there we would go to random missions and just film tricks or ideas at weird spots. And that was really fun because there was a lot less pressure thank those New Balance sessions. So it was just kind of like, roll on whatever we got that day.

After filming for a month you forget what you even got. Once it’s processed you’re like a little kid watching it, like “Oh my God, we got that?! I can’t believe it.” And then I think you’d always be like: “I think the roll didn’t end early and I might have gotten it, but I don’t know, we have to wait.” I think it’s kind of cool, to have to wait and be patient and it feels like we’re doing something that was done in the past. So it’s kind of cool to draw from that a little bit.

Yeah, it’s almost showing a slice of what it’s like to make a video part, but also getting some of those tricks in real time as well.

I just think this project is really special because of the fact that it was so low-key and we stacked tricks on film for so long kinda by accident.

It’s kinda rad that I shadowed you during the making of these parts. It’s cool to document that and also learn about how skateboarding works at the same time. I saw the process of what it’s like to film really intense high-level parts. And I got pretty inspired, too, by how long you guys will work on these parts in secret basically. You just chip away at footage as opposed to my surf filming background, where sometimes you can get all the footage you need for a surf video in one big swell event… But you guys go quiet and make these heavy parts almost in a vacuum. And that is cool to see. Using 16mm film to put that experience in a time capsule was really rad for me.

I don’t think I’ve never made something like this, or been a part of something like this. I feel like you can plan out a normal video part. Like, as in “I’m going to try a trick on Saturday, if I don’t get it, whatever, we’ll just keep going back.” But with this format, you only have so much film in a roll to shoot and you’re like, “OK, we’re doing it.” I don’t know. It’s interesting.

Even seeing what we have, it’s kind of crazy because over the course of a couple of years you can get a lot of footage and you can shoot at random spots that won’t exist anymore, like the roll-on grind in Santa Ana or the weird light pole that fell down that we skated. Those kinds of crazy moments that you go like, “Wow, only by being there could we have got that.” Like being in the car and showing up and lurking in the moment. That one weekend was your only chance to get that.

We saw the light pole off of the freeway…

It’s almost been like documenting the making of a skate video part. Or even multiple ones… What do you think was cool about having 16mm sort of incorporated into years of just tagging along on these sort of quests to make a video part?

First of all, 16mm feels nostalgic to me. Seeing yourself in that format is cool, kind of no matter what you do looks awesome, and no one makes videos like that anymore. So it’s cool to know that we patiently worked on that for three years and you tagged along. It shows the truth of why sometimes stuff doesn’t work. Sometimes stuff does. Like you mentioned before, just by you tagging along and randomly filming something at a spot and in a month, it doesn’t exist anymore. The whole building’s gone… All those little things are just really cool and kind of timeless. And it’s much more in the moment. After filming for a month you forget what you even got. Once it’s processed you’re like a little kid watching it, like “Oh my God, we got that?! I can’t believe it.” And then I think you’d always be like: “I think the roll didn’t end early and I might have gotten it, but I don’t know, we have to wait.” I think it’s kind of cool, to have to wait and be patient and it feels like we’re doing something that was done in the past. So it’s kind of cool to draw from that a little bit.

Would you say that there’s a certain type of spot or level of trick that you’re not going to be able to get on film where you consistently try and try and try? You know, there have been multiple times where I’ll film and I ask “Should I film this?” And you’re like, “No, unless, like, I’m getting close”, you know… What works for 16mm?

Sometimes we’ll go to a spot and it’ll be a no-brainer. Like OK, I’ll try a couple and then if I know I can do it we’ll try to film it on 16mm. There have been times where it feels like I wasted your money burning through film, but then there are other times where I’m deep into a battle and we just make like a connection and we’re like, “OK, this is the try.” And then it doesn’t work, haha.

Or it does! Like the ollie over crook at the bank.

Yeah. Or it does work and it’s like a crazy feeling… So you never really know what a 16mm spot is. But I think that’s what’s cool about our film is that we have real tricks, we have fun tricks, we have weird spots. We were able to do this for a good period of time. So we have some cool stuff and I feel like that is probably rare today. But I know like twenty years ago they would have made montages that way. They made a whole skate video this way. The birdhouse video The End. It’s kind of mind-blowing to know what people in the past went through versus like how you can just digitally shoot anything today. Props to 16mm skate videos or any 16mm videos in general.

Can you explain the different levels to filming parts… It’s been really interesting to document everything, from your New Balance String Theory part to WKND to now MUSEUM and so on. This project is almost like a behind-the-scenes of what it’s like to grind and try really hard.

For example, in the WKND part I couldn’t get the opening nose blunt like I wanted and I just accepted it after seven times… There are tricks in skating where there’s a lot of luck tied in and you’ll never know if you’ll really do it, but one can magically work. And the fact that you can maybe capture that on 16mm is always tempting. Like the ollie over crook that accidentally worked because somehow my weight was on the ledge perfectly… but like a million tries didn’t work.

Not always but I’ll watch videos from Europe or Japan and I’ll see some ideas they have and I’ll be like, “Oh you know what? There’s this spot in Glendale that’s like kind of similar to that.” I wonder if I take inspiration from where they left off. But I add my own twist on it.

I was like rolling every five tries or something. And like that one worked…

Yeah. The fact that those magical things can happen is I think what makes 16mm even more special than digital is because…

The shit has to come together.

Yeah. It has to come back, it has to come together either accidentally or like you vibe together on those couple of tries. And I’m like, “OK, fuck I know Matt’s filming 16mm, I really gotta go for it. I can’t fuck up…” But there are tricks like that on digital where I’m like, “OK, shit Grant and all the dudes are here for the seventh time, I have to do it this time,” but I still can’t do it.

What kind of trick ideas do you get psyched on? Do you always aim to approach something differently?

Not always but I’ll watch videos from Europe or Japan and I’ll see some ideas they have and I’ll be like, “Oh you know what? There’s this spot in Glendale that’s like kind of similar to that.” I wonder if I take inspiration from where they left off. But I add my own twist on it. I try my twist on it, pulling from skateboarding’s past mixed with a combo of cool ideas from today’s skating.

Where do you come up with those ideas for the themes of your parts? Are they a reflection of your personality?

I want it to be hard for me to do and to look interesting. I don’t want to film something just to film it. I want it to be difficult for me at least. The past inspires today for me. I get more hyped on old stuff. It’s like the same way I get stoked on special effects in old movies instead of CGI. I would say I’m inspired by similar things to those guys. But where I live dictates how I skateboard as well. I don’t have cellar doors. I don’t have Barcelona banks everywhere… We have a lot of blown-out L.A. spots. And you just kind of work with what’s next to those spots. It’s tricky. I think when every skater says fuck L.A., it’s because it’s really fucking hard to skate here, and going to Australia or Japan or Europe is probably way more fun because they haven’t been skated that much. These zones have been skated by the best skaters ever for like 40 years or longer, so it’s hard to find inspiration and motivation.

You’ve got to reach deep into the bag.

I swear L.A. or Orange County has to be the hardest place in the world to skate. In Orange County, there’s suburban apartments built in like 2016 behind you. It looks gross. But that’s kind of what’s cool about it, the challenge of making it look interesting with filming and the tricks and spot all together. A lot of people can easily say, fuck this place. But it almost feels punk rock to be like « “No, I’m going to stay here and try to fucking film in this crappy area and try to make something cool of it to inspire kids like me growing up.” » Not everyone will agree with that. You know, a lot of people will be like, fuck this. I don’t want to film in L.A.

I feel like part of the reason I do that is because of how far skating’s progressed. It’s hard for me to keep up with today’s skating. I would think… That’s the truth. But I’m also inspired by people skating cool spots and cool-looking things.

What makes L.A. a difficult place to skate?

Everywhere you go, the best tricks have been done. They’re getting skated on Instagram. It’s hard to find new things because it’s been skated for so long. Everyone’s found them. So there’s that side of it. Also a lot of rad skating comes out of Europe or the East Coast or Asia. And when you watch their footage, it visually just looks cool versus a suburban area of Orange County. And driving everywhere… every spot is like 25 minutes away. It can cause a lot of stress, I think.

Is that why you feel like you need to find spots that haven’t been skated before?

I feel like part of the reason I do that is because of how far skating’s progressed. It’s hard for me to keep up with today’s skating. I would think… That’s the truth. But I’m also inspired by people skating cool spots and cool-looking things. And I know those things exist, they just take a lot of work to find them. And then when you do find them, sometimes you need to fix them. And all that takes a lot of time and patience. So I feel like it’s partly for the reward of that. It’s cool because I know that inspired me when I was little, when I would see like a local video and I would be like « “Whoa, where did they find that? That’s so cool.” » And then growing up and seeing videos made by companies and they’d be skating different areas of L.A., I’d be like « “Where’s that school? I’ve never been there.” » So I guess it all stems from like watching cool stuff to get inspired. I guess I just want my footage to look like that.

So what on average goes into like a gnarly video part that you’re proud of?

A video part that I’m proud of takes…a lot of looking for spots and a lot of fixing them and hoping that the ideas translate in the footage because sometimes they don’t. But a lot of the times they do… It’s a lot of hard work. And I feel like since the Zero video Cold War, that I just have never stopped filming or looking for spots or fixing them. It’s like an addiction. I’m hyped to make cool things happen in a weird area that I live in that’s not like globally the sickest place to skate. It’s a challenge and it’s rewarding. And I don’t know if everyone likes it, but I just know I try hard and I’m proud of it. I like it and I’m thankful that I have sick sponsors who support that too.