Words by Yentl Touboul | Photography by Matt Martin | Photocopy Club Photography by Aidan Frere-Smith

This interview was originally published in Volume X, January 2022.

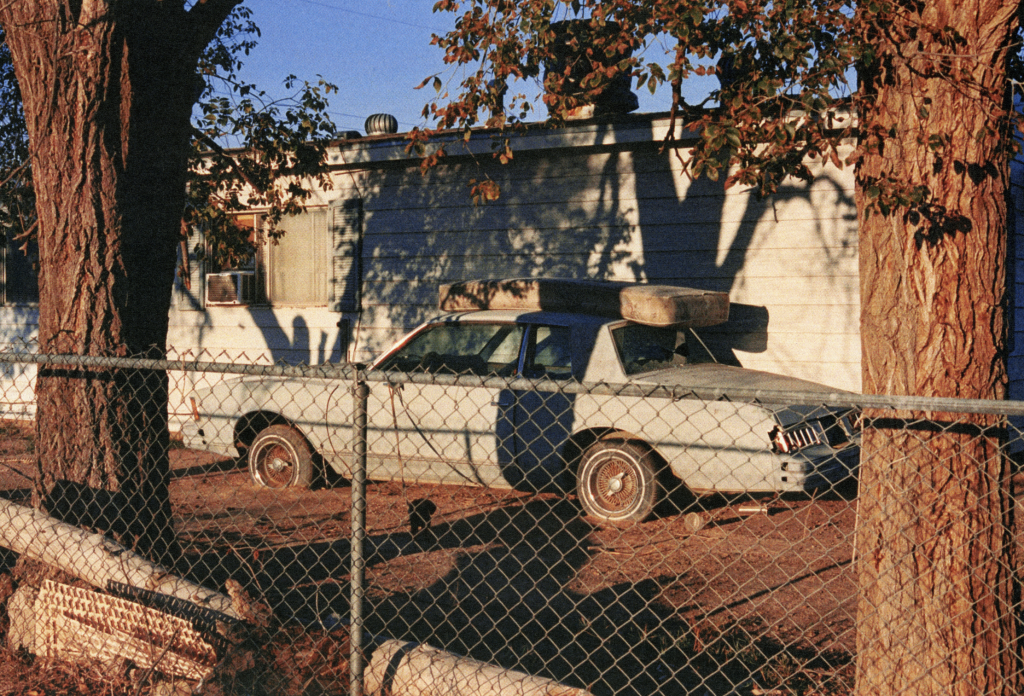

Matt Martin (@luckygoldteeth) is a British photographer, zine maker and publisher raised in Devon, England, and based in London since the past 8 years. We first heard about him through his American Xerography book, which beautifully depicted rural America through the medium of Xerox printing.

After digging further, it turns out that Matt’s work goes far beyond his occupation as a solo photographer: on top of running several galleries over the years and now being the curator at the Photobookcafe in London, Matt has been enabling hundreds of photographers around the world to to have their work exhibited through his Photocopy Club group shows.

Both his work and approach—empowering communities around the world through photography— has been an inspiration, and with our tenth issue coinciding with the tenth anniversary of the Photocopy Club, we thought it was the right time to highlight his work and learn more about him.

When did your interest in photography start, and how/when did you start taking photographs?

It all comes from skateboarding. A pretty generic answer I know, but it was that and punk rock. Growing up, my room was covered, floor to ceiling, with posters and tear sheets from magazines. I think more than the actual skate photos or band photography, it was the images of behind the scenes that caught my eye. Those photos in Thrasher where people are just hanging out, drinking or smashing car windows. There’s that amazing photo of Jake Phelps that I always loved, of him just after a car crash covered in dirt with the car on its roof. That’s the stuff that caught my eye. But back then I wasn’t looking into who took the photos, they just existed in the magazines that I bought every month.

I had a point and shoot when I was around 10 and we would just take photos of us riding bikes or skating, but I didn’t really get obsessed ’til I was around 17. I was doing Media Studies at college and hated it. We were allowed to do a two-week course in photography doing black and white processing and hand printing, and I just fell in love with it. I quit the media course and joined the photography one. Then I started shooting everything. Bands, skating, graffiti, fashion, photos of friends hanging out. I couldn’t stop.

At that time, Flickr was huge. I started to build this community; I would share my photos and follow other young photographers shooting the same stuff. I was also really in to graffiti but wasn’t the best painter, so I started taking photos of the guys I would paint with. This was around 2004/2005. Street art was getting really big then. I found out about JR, who was making photos in Paris and then pasting them around his city. I had used copiers in zine-making but when the whole idea of being able to wheat paste your photos around the city came about, that really got me. Like a giant zine for everyone to see. I would take my photos to the copy shop and get A1 sized prints, then I would just roam the city all night sticking up my photography. I would try to come up with new ways to show the work. Because I wasn’t that good at graffiti, still being able to shoot gave me that rush of going out and painting but using my photography rather than paint.

Have you been to art school?

I didn’t go to art school, but rather than university, I did an extra one-year photography course at the college. It never really appealed to me and I didn’t like the pressure they put on you to go to university. So I worked in a skate and surf shop for a bit and then got a job at the local Snappy Snaps, which is a high street film lab. That was all I needed. I got cheap film, photos processed for free and I could make photo zines to give to mates. It was perfect. I’m pretty driven and self-motivated, so I felt that going straight into work would be better for me. Then I could make money working in the industry and do my photography for the fun of it.

Tell us how things evolved from there—at what point did you decide to make a living from photography?

I worked at the lab for about three years I think. In between that I started to curate small group exhibitions in Exeter. We would find disused shops or spaces and do pop-up exhibitions with a mix of photographers, illustrators and musicians. I really enjoyed the idea of working with photographers, so I started a blog called WE ARE LUCKY, which featured photography, made group zines and did interviews. This is when I started to see a career moving forward.

Being from a small city far from London was tricky. I would make zines and send them out to photographers I liked. No magazines would give me work as I was too far away. I was going to open a shop with a friend that would sell artwork and t-shirts etc. We started planning the project and looking at spaces. But then my Grandad died and I got £3000 in inheritance. So I decided to pack up my bags and go to America. New York was where I really wanted to be. I had been going on and off over the last few years and had built a good group of friends. So in 2009, I went to NYC for three months. I did some nude modelling for photographer Ryan McGinley, and did some interning for Tim Barber, who was running Tiny Vices at the time. But New York was pretty hectic and I kept running out of places to stay and after being in some hostels for a week or two, I headed to see a photography friend in Baltimore. Baltimore was way more up my street. A smaller city with great bars, music and more of a punk and DIY art scene. So after being there for another few weeks, me and my friend Alex decided to do a road trip down to Florida and back. This was the first road trip in the states I had done. I couldn’t drive at the time so Alex did all the driving. But that was the trip that got me hooked. Photography and the open road.

When I got back from the states, I decided to move to Brighton. There was a great photography scene happening there and a good punk music scene too, so I moved there at the start of 2010. I quickly tried to embed myself in the photo scene. There was a studio called Garage, run by a photographer called Kevin Mason. He did graffiti and shot fashion and I thought this would be a good place to start. So I walked in and asked for a job. I started helping there on my days off between a job in a shoe shop and doing telesales. I would paint the studio floors, be a runner on shoots and make the tea. Kevin gave me my first solo exhibition in the studio, which was all the work I had shot on the three-month USA trip. It was called ‘Eat Well, Stay Fit and Die Anyway’. This is the point where I started to think I might be able to have a career in photography. In 2011, he gave me a full time studio assistant job and I started to run a gallery space called Create that was part of the studio.

Looking at your work, it seems like your approach is inspired by a DIY/punk approach. Where do you think this comes from?

It all comes from skating, graffiti and punk music. It’s making it work with what you have. You want to have photos in a magazine? Start a zine. You want photos on a gallery wall? Wheat paste them on the street. Want to play a gig? Go busking. Make shirts, learn to screen print. No one’s going to learn that trick for you. DIY or DIE.

Your love for the landscape and your photography is striking. Do you sometime shoot people as well? Or do you feel more comfortable shooting nature/still life?

Thank you. I used to only photograph people really. That’s the photography I was into. Photographers like Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, Ryan McGinley, Corrine Day and Ed Templeton. That whole diaristic, point and shoot style of photography. But as you start to study photography more and you come across people like Lee Friedlander, Robert Frank, William Eggleston, Justine Kurland, Alec Soth…your photographic knowledge and style starts to expand. Also, my love of the photographic book was growing as I started to collect more photo books and zines.

I think there were a few things that took me away from photographing people in my day to day life. I started to become shyer with a camera. Not needing so much to document the moment as much. But also maybe those moments were starting to not be as interesting as before. You’re not out skating all the time or climbing rooftops or doing stupid shit at parties. Then you get to a point where you’re sat in the pub, or out for dinner and you start to leave your camera at home.

Photography started to change for me about five years ago. I wanted to work slower and more alone, not just for myself but for my subjects. I love walking with a camera. I started to go to LA around 2016 for book fairs and I just walked around the city. I would go for miles, and because everyone drives in LA, it’s just you on the street, stuck in this weird no man’s land. This is when I discovered the work from the New Topographics era and photographers like Robert Adams and Henry Wessel, and it really played a big part in changing what I was shooting. I became more transfixed on smaller details of the street and the architecture of the modern landscape. I finally felt like my work was me and bringing Xerography back into my practice really let me take hold of my photography and make work that started to have a voice. This is when I started on American Xerography Vol 1.

Can you introduce the technique of Xerography for those who might not know what it is?

Xerography comes from two Greek words meaning ‘dry writing’ as it doesn’t use any liquid. I’m not sure if you want me to explain the tech side of how a photocopy machine works, but what I like about photocopying is the use of toner and how particles fuse to the paper through a positive charge. To me using a photocopier is like being in the darkroom. I love the instant nature of it and how you can degrade something the more times you print it. The old Xerox logo from the 60s had the tagline, Products for Xerography around the logo. That’s the logo we used and redesigned for the Photocopy Club project, changing the it read: Xerography for Photography.

At first, the method of Xerography—basically shooting with good lenses/cameras on expensive film stock, and then printing them on the cheapest printer around, rather than creating proper prints from negatives—can seem a bit like a contradiction.

How did you first start doing Xerography, and what got you hooked?

I think with making photocopied work you don’t need all that other stuff. You can shoot on a thrift shop camera with cheap film and still make a great photo. You can go really heavy with the contrast or really dark with minimal detail. But also I think it’s about working out what kind of images work well when photocopied. But I also kind of like the contradiction of what you’re saying. Why because the final process is cheap should the other aspects of the work lack in quality? It’s the whole process that makes the work interesting. But right now I’m also really into colour darkroom printing and after doing some classic colour prints, I want to bring Xeroxing into the darkroom. But I’ll tell you about this later.

Let’s talk about American Xerography in Colour. What did you want to capture in this series?

This project was to expand on what I had done in the first book. But also, it had been a dream of mine to drive solo across America, so the act of doing it was more important to me than the work that might come out of it. The idea was just to take it in, to document what I saw, with no real comment or story. I just wanted to see all of America. I had done coastal trips and one trip from Oakland to Baltimore before, but never alone and never full circle.

My work over the last few years as I said has become slower, more isolated, with no people. Trying to find moments in the landscape that can’t be pinpointed in time. I like it when you look at a photograph and you can’t tell if it was taken yesterday or 50 years ago. So the book covers those moments. The double take, screech on the breaks moments. I quote in the front of the book, “In this country a man without wheels is only half a man”, which is from a Robert Frank film called Candy Mountain from 1987. This quote was meant to embody my thoughts on America. The vastness, the aloneness. How the car has changed the landscape, how it’s made many connected, but many more isolated.

I was also looking at a lot of old National Geographics at the time, so this really affected the colour palette of the images. Warm oranges, deep blues and greens with vibrant reds, which come from the basis of advertising and dye transfer printing from the 60s and 70s. The book took about a year to edit. And even though there are not a lot of images in the book, the size, design and layout was something I needed to sit with and keep viewing and changing. In the end I actually think I went with the first edit and design, but you need that time with a project like this. The photos need time to move away from when they were shot and take on their own lives.

Can you tell us about the journey itself?

So the whole trip took two months. The plan was to make it to New York for the Printed Matter Art Book Fair which was halfway through the trip. I was also going to make zines at different mom-and-pop style printing places as I went, and bind them on the bonnet of the car. So I started in Oakland and headed south, down to LA. This part of the trip I had done before so the route was familiar. It wasn’t until I started heading west through Arizona and New Mexico that I began to realise the size of the country. The horizon stretched out in front of me, the road with no bends, and the endless desert. I stopped off in a few towns. Visited a zine library on an indigenous reserve. I tried to keep off the freeways as much as possible. Every time I would see a town of interest or something off the road I would turn around or pull up and take a walk around.

From Texas onwards I was driving about eight hours a day. Across the Mississippi, through Alabama, up to Tennessee and along the borders of Kentucky and Virginia. I made about ten zines in total, along the way. I met up with friends in NYC and had them for sale on a table at the fair.

After that I headed up to New England and then over to Detroit and Chicago. Through Iowa and the Dakotas. This was October time and it was starting to get cold. For some reason I only brought a denim jacket and by the time I was up in the mountains it had started to snow. At some points I didn’t see another car or person for about three hours, driving through the dark in heavy sleet. I would pinpoint towns with interesting names on the map, not searching what might be there. Just heading with a feeling. Then from there I went to Portland and Seattle to see old friends and then down the coastal road, the 101 all the way back to Oakland. On the last day of the trip I met a girl and fell in love. But it didn’t last.

Were there places you wish you’d stayed longer and had more time to shoot?

I would like to spend a bit more time in the south. See more of that southern coastline. Maybe there is another project there at some point. Right now though I want to focus on making work closer to home.

Do you have anecdotes from the road?

It all kind of bleeds into one. Nothing that crazy. I stayed in mostly Motel 6’s which can be a bit rough depending on the town. I stopped at one in New Mexico, and as I got out of the car this hench dude with a full neck tattoo popped up from behind a dumpster with his heavily pregnant girlfriend and asked if I would drive them to the casino, and if I did he would roll a hand for me. One part of me was like, that sounds pretty fun. But the other part of me had driven for eight hours so I politely declined. Then when I got to my room, it was one of those motel rooms that had the door kicked in so many times it has about five locks on and the peep hole is stuffed with paper. Shouting from the room next door started to happen and the slamming of doors, then this woman got picked up by a Cadillac where the windows were so tinted it looked like they had been painted with black paint.

All in all I met some great people. It’s fun when you travel solo. You take more risks, end up talking to more strangers and have no issues driving for hours or taking wrong turns. It’s all part of the adventure.

It seems like you have a certain affinity for the USA, and that can also be said for a lot of landscape photographers. Do you have an explanation for this ?

In some ways it’s a rite of passage. This idea is laid out for you through film, books and music. You’re drawn to this idea of the open road. For over the last decade it’s been a big part of my life, but now with the restrictions on travel, it’s really opened my eyes up to the UK and the landscape here. Why do photographers like America? In some ways I guess it’s easy. You can turn your camera anywhere to see something to photograph. I feel it’s harder to do in other countries, and maybe this is because they are always unfamiliar. America through film is ingrained in how we see. By looking at more British landscape work, I’m trying to train my eye to open up a similar feeling here. To embrace rather than push away. I think if you look at Paul Graham’s book A1—The Great North Road, it’s a great example of the American Road trip, but in England.

At what point do you decide the style for a certain project? For example, whether you’re gonna shoot colour or black and white, or do it with traditional photography, or go through the Xerox process?

I like to play with my work over time. I like that you use it right away or come back to it. Hand print it or Xerox it. Crop it or blow it up. I find new images all the time in my work. That’s how I have tried to get into the habit of shooting everything, even if you don’t see the image you’re looking for straight away. You know something is there, and you can come back to it later. I like the mixture of film and digital, or shooting on your phone. I go through phases of styles and genres in photography. I think because I work in the photography industry but not as a photographer, it means that I still have the freedom and playfulness. I don’t need to stick to one style, I don’t need to make money from taking photographs, and this means it still excites me. It’s a passion and I’m still finding new ways of working. With this new project I’m working on, it’s really starting to grow with the idea of mixing mediums; that really excites me.

Can you speak about the gear involved with Xerox printing. I know the basic concept is to use any printer available, but for someone like you who pushes the concept a bit further and does complete books out of it, have you become more specific about the printers/ink…etc. you use? Sort of like any photographer does with camera and lenses?

When working with photocopiers the best thing you can do is use different paper stocks. This is what makes it for me. It’s how the toner sits on the paper that gives the image its final feel. When I first started using copiers I would go to the library or cornershops that had cheap printing, just to see what sort of effects you could get out of different machines. To start with I was just using black and white machines due to cost. A photographer I know called Valerie Phillips bought me my first A4 Xerox copier to help me out with making zines. In return I would make zines for her and what would become an ongoing series—every time she released a book, we would do a bootleg version too.

When speaking to photographers about their inspirations, cinema often comes up as a main topic. Are there specific movies/directors/directors of photography that are an inspiration to your style?

Wim Wenders is huge for me. The colours in Paris Texas are unbelievable. I loved the work of Larry Clarke and Harmony Korine growing up. Rebel Without a Cause and Midnight Cowboy. The Beautiful Losers film by Aron Rose and Everybody Street by Chyel Dunn. I also love watching old information films from the 50s and 60s in Britain. Old gangster films like Get Carter are really good too. So quite a mix.

I’ve seen you’ve had several talks with Ed Templeton published online. Can you tell us about how you first met him, and how he was influential to your universe?

Ed was and is a childhood hero of mine. His book The Golden Age of Neglect was one of the first photography books I ever owned. I was asked to do a talk with him at the Photographers Gallery when he released Teenage Smokers 2. It was pretty crazy to be sitting in front of one of your idols, doing a talk and in an institution you admire like that. A few years later I also did a talk with Ed at Photo London in Somerset House, which again was a crazy situation. Being invited to talk about zines and skating in a place like that. It had also just been a week since Ben Reamers had passed away, so that talk was dedicated to him. The London skate scene was hit by that really hard, but the work that the Ben Reamers Foundation has done since then has been amazing and the conversations around mental health and more collective skate crews for womxn has pushed the scene to new levels. I feel that that’s what Ed is all about. He has always combined the ideas of art and skateboarding to help people, and he created one of the most forward thinking skate companies with Toy Machine.

With the world becoming more and more digital, fewer people seem to be working with negatives and making prints with their hands. But it seems like an important process in your work. Why is it so important to you?

I think this idea is changing again from the rebirth of analogue photography in 2008. Working for a photo lab, I see more and more young people getting into film again and having an interest in hand printing and darkroom techniques. There is now this new generation that never grew up with anything analogue and sometimes not even their parents used film. So the interest is coming back and I think that with the growth of the YouTube film community, we are seeing more and more people back into or starting to shoot on film and making prints. I really jump between the two. If I’m wanting to set myself a goal of shooting a project and making a zine in a day, I use digital. For longer projects I shoot film, and for those everyday shoots I have a mixture of film and digital.

We know that beside your work as an artist, you have several extra projects, one being The Photocopy Club. Can you tell us the concept behind it, and where all it all started?

The Photocopy Club started in 2011. The whole idea was to make an open call that was affordable. Not just for myself but for everyone involved. I had been doing these pop-up style exhibitions for a while, but always struggled with finding a way to have lots of photographers involved, without sky-high costs. So the idea was to level the playing field, take away this concept of photography being shown on four white walls with an unattainable price tag.

The concept was to do a call-out for photographers to submit their photography, printed using a black and white photocopier, or a cheap large format printer. Really to have to spend no more than £10 on printing. To sign and date the prints on the back and then post them to me. No theme, no age bracket, no restrictions on where you live. Just shoot, print and post.

We also wanted to make photography affordable for people to actually buy the work too. So all the prints were £5 and you could buy them on the night and take it off the wall when you leave.

The first exhibition had around 60 photographers showing around 300 images, and from there it just blew up. Ten years later, I have travelled the world, met amazing people, showcased the work of over 500 photographers, all because of photocopies.

Why do you think the concept took off like it did?

I think it’s just simple. There’s no issues with money, which is a big problem when you submit work to some of these photography call-outs. Everyone is equal. There is no hierarchy as everyone has to print on the cheapest machine they can find. We have had work come from all over the world— every town on the planet has a photocopier, pretty much. I love getting submissions coming in covered with stamps from all over. People draw cool pictures on them and write notes. People just really love to be part of something. Even though The Photocopy Club is just me doing it, I always say ‘we’, because the shows wouldn’t be what they are without everyone being part of it. It’s a giant collective, making a giant zine, that everyone can take a page from.

Can you go through the milestones of the photocopy clubs throughout the years, and what were highlights for you?

I mean there’s been a lot. In ten years we have packed a lot in. I think the first London show was a big one for me. Simple start, but being this kid from the countryside who never thought I would be putting on a show in London was pretty nuts. It was a small gallery but rammed and it meant a lot for people to come see this project on its second show. Next was probably going to Hong Kong. The first exhibition outside of the UK. Pretty crazy, right? Flying halfway across the world to do a DIY punk style exhibition in the middle of Hong Kong’s largest shopping centre. Then doing our family politics show at the Jerwood Gallery was a big one. It felt like the project was being accepted by the photographic industry and community as a project of real importance. That opened a lot more doors, and helped with bringing The Photocopy Club to an even wider audience. We have also done three Xerox and Destroy exhibitions through The Photocopy Club, with the theme of skateboarding. They have been some of my favourite exhibitions and I’m looking forward to doing a fourth in 2022. Maybe we can do one in France with you guys!

Can you tell us about the ten-year anniversary event that took place in December?

The ten-year anniversary show took place on the 9th of December. It was something I had been planning all year but it kept getting pushed back. I managed to find a venue for it and we had about a month and a half call-out time for the submissions. I hadn’t done a Photocopy Club show in over two years by this point so it was amazing to have a call out again. No theme, one night only. Like the old days.

The response was incredible, with lots of new photographers getting involved as well as people that had been in on the project since day one. We had over 230 photographers in the exhibition and about 300 people came through to check it out. I love doing one-night exhibitions. The rush and excitement of setting it up and then with everything being for sale at the end, it’s all pulled off the walls, and that’s it, done. It was a great way to finish 2021 and it’s got me hyped to bring back The Photocopy Club in 2022.

It seems like in a lot of your projects, a sense of community is key. Do you think that curating, and having that sharing relationship with your peers is important when you are an artist?

Community is everything. That’s what holds you up. You need that sense of belonging. To bring artists, skaters, musicians, etc. together is what makes this all work. Look at how many DIY parks have been built over the last two years alone. People just came together and fucking did it. It’s the same with this. You can come up with a good idea, but it’s the community around you that makes it great. DIY always has community. It may be Do It Yourself, but we couldn’t do ‘it’ without each other.

Check more of Matt’s work here.